Sunday Essay: Telling Stories

Journalism Treads the Line Between Empathy and the Need for Narrative

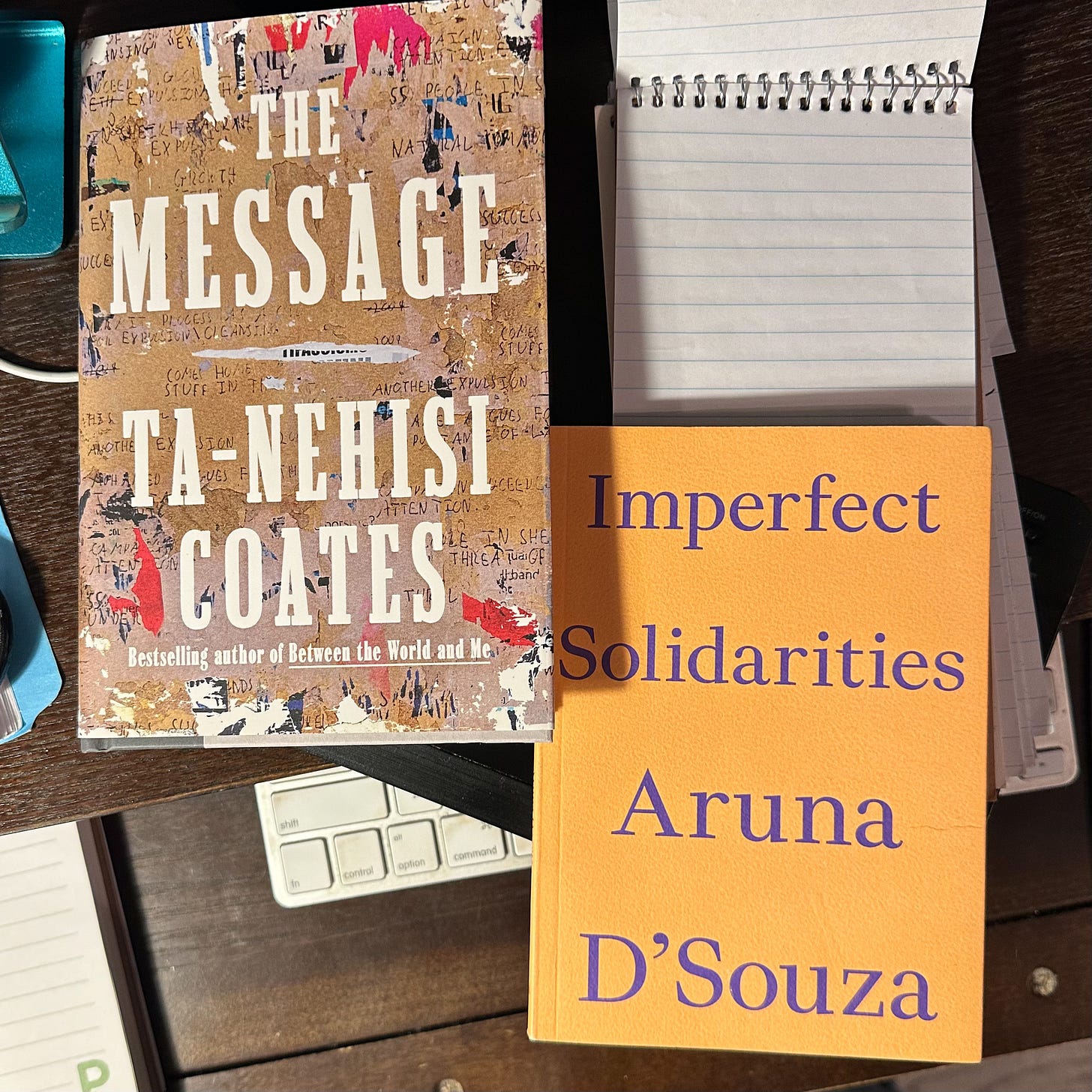

Two thoughts about writing and politics. One from Aruna D’Souza, the writer and art critic. The other from Ta-Nehisi Coates, the journalist, essayist, and novelist. One questioning the idea of empathy as a political motivation, the other

D’Souza, in her book/essay Imperfect Solidarities1, writes that a reliance on empathy as a political tool “puts the burden on those being victimized to narrate their conditions in order to ‘change hearts and minds’ — a horrible burden, especially for those who are reporting the violence while experiencing it in the most heinous ways” (15).

Coates, in “Journalism is Not a Luxury,” the opening essay of The Message2, argues for a “tradition of writing” in which the writer is “drawing out a common humanity.” It is “indispensable to our future, if only because what must be cultivated and cared for must first be seen” (16).

The arguments might, on their face, seem contradictory. One demands the right of “opacity” for what the West usually sees as “the other.”

“The refusal of a politics that relies on empathy to build solidarity is, for people of the global majority especially, a matter of self-preservation” (52), writes D’Souza. She sets this against “Western ontology’s demand for transparency — a demand to know the other (whether in individual or a culture or, in fact, however otherness is being conceptualized in the moment.”

The West’s need to know is never innocent curiosity, and rarely is it a simple desire for entanglement — it almost always takes place with a relationship of domination, and thus whatever knowledge results is essentially derived without real consent. (52-53)

Empathy, she argues, ultimately is not about the oppressed, but about the oppressor or those who have benefited from the oppression. The intellectual act of empathizing is one in which we are asked to reconfigure “the other” into terms we, the dominant/dominating group, can understand. It is an act of translation, D’Souza says, that recasts “the other” as “just like us” and robs them of their individuality. This argument is similar, I think, to some of what Ibram X. Kendi’s argument that racism is not about hatred but about imposing stereotypes, erasing the person, and then imposing a set of structures that keep in difference in place3.

Journalism, writing, storytelling, as Coates describes it, is an act of empathy, or a kind of empathy, a recognition that there are others and that our job as writers is to tell stories, to create fully fleshed out characters (in fiction), or present real people as clearly and honestly as we can. Coates describes the writer as being like a map-maker “standing at the edge of a sprawling forest.” The map-maker’s job is to map the forest “with such precision that anyone who sees the map will feel themselves transported into the territory.” Where the writer and map-maker differ is that our job is to “pull us into the wilderness,” and that means entering the forest.

You have to walk the land. You have to see the elevation for yourself, the color of the soil. You have to discover that hate ravine is really a valley and that the stream is in fact a river winding south from a glacier in the mountains. (16-17)

Coates is looking for a “world made clear,” in which the stories allow us to get beyond the theory — beyond the jargon and academic language that obscures lived experiences.

This is what I try to teach my students, that our job as journalists is to tell the stories of those willing to share their stories, while also using our skills as researchers and writers to ferret out what the powerful wish to keep hidden. I think what Coates is outlining — and what the good journalist does — is empathetic, but it is an empathy that is different from what D’Sourza describes. We do not need to feel — or should require a feeling of — empathy to act politically, as she says, but we do need to see, to understand what others in the world face. I teach a section in my digital news writing class on longer form writing, using early and recent news reporting and writing ranging from Walt Whitman on the Civil War to Abraham Cahan on Ellis Island to Joan Didion, Jimmy Breslin, and Rachel Kushner.

Students respond to these pieces on a lot of levels, including the way they draw readers into worlds they otherwise would have no contact with. When they read Didion’s “Slouching Toward Bethlehem” and see themselves in her, as the outsider being invited into the San Francisco hippie movement, they come away with a surprisingly nuanced view of hippiedom, especially because most students do not have more than a fleeting connection to that time period and that space.

When they read Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah’s “A Most American Terrorist: The Making of Dylann Roof,” they see Roof and his mass murder in South Carolina for what it is and where it comes from — but because Ghansah is their tour guide, they are forced to understand the complexities represented not by Roof but by our reactions to Roof.

Are these examples of the damaging kind of empathy that D’Souza is concerned with, or the “world made clear” that Coates demands from writers?

For the journalist and the fiction writer, this not a theoretical question. As I watch from afar the genocide unfold in Gaza and see the images of destruction, the damaged bodies, the faces of orphaned children and try to make sense of what I see, it is important to avoid the kind of pitying reaction that makes our charity about our responses. I wrote earlier this week about “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” and the way it allowed the privileged in the West to substitute charity for action. It is the same kind of dynamic we see on late-night TV, with its use of tragedy porn to get us to donate to the groups like Save the Children, the ASPCA, and others collecting money providing needed aid but doing nothing to prevent the violence or the need in the first place.

TBT: Do They Care It's Christmas

The intentions were good, and the song has become a staple during the Christmas holidays. Still, “Do They Know It’s Christmas” has not aged well. Like the American effort organized by the late Quincy Jones, the song is weighed down by a history of western colonialism, or what anthropologists call an ethnocentric view point.

These ads play on our guilt to raise money, asking nothing more of us than that we write a check, and absolving us of other action. We donate blankets and water to homeless camps, but do nothing about an economy that is structured to create a deep inequality that drives people into the streets or makeshift camps in the woods. Our actions make us feel better, but do very little to improve the lives of people we see as unlike us, and that may leave us feeling — to quote the most offensive line of “Do They Know It’s Christmas?”: “Thank God it’s them instead of you.”

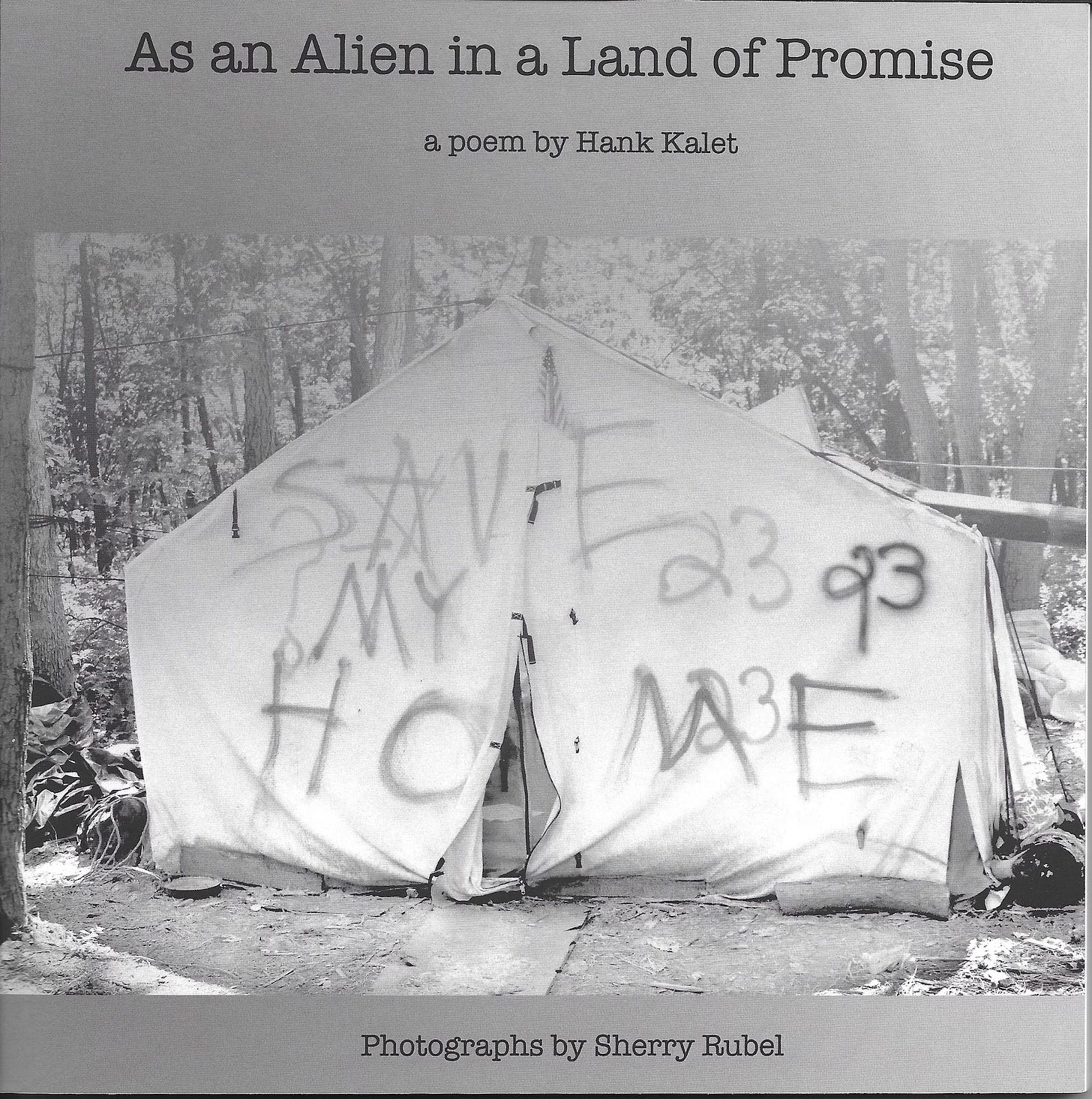

Journalists are complicit in this failure. I am thinking of my own reporting as I write this, of the year I spent interviewing and writing about the tent encampment that existed for years in Lakewood, and the book I produced4. My intention was to do what Coates argues for, to map out the dense forest, to make it impossible for readers to ignore the causes that led most of the men and women I met to live in tents. It is my intention with all of my journalism — which is why I continue to cover homelessness, international migration and immigration, and so on. But am I asking my reader to empathize, to see themselves in the lives of these “others”? If so, aren’t I doing a disservice to the subjects of my writing? Aren’t I erasing these men and women and turning them into symbols?

My intention is — to quote Coates — to do more than tell stories. “(W)e are charged with examining the stories we have been told, and how they undergird the politics we have accepted, and then telling new stories ourselves” (19).

“You cannot act upon what you cannot see,” he says. And you cannot act unilaterally, I would add. Those of us with privilege need to understand that.

Aruna D’Souza, Imperfect Solidarities, Floating Opera Press, 2024.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Message, One World/Random House, 2024.

Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped From The Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, Bold Type Books, 2016.

Hank Kalet, As an Alien in a Land of Promise, Piscataway House Publications, 2016.