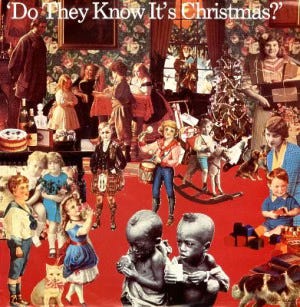

The intentions were good, and the song has become a staple during the Christmas holidays. Still, “Do They Know It’s Christmas” has not aged well. Like the American effort organized by the late Quincy Jones, the song is weighed down by a history of western colonialism, or what anthropologists call an ethnocentric view point.

Recorded and released to raise money to feed the victims of African famine, the song feels like a late-night TV commercial for UNICEF or the ASPCA. It is a kind of tragedy porn, which allows those of us in the “developed world,” the moneyed countries, to feel good about ourselves for caring about these “poor souls” in that faraway land where bad things happen.

I remember when the song came out, how important it seemed at the time. Bob Geldorf, who co-wrote the original, summed up its impact recently when announcing the release of “an all-star splicing of the three previous official versions” to help celebrate the 40th anniversary of “Do They Know It’s Christmas?”

Geldorf told The Guardian that the song “tells the story not just of unbelievably great generational British talent, but still stands as a rebuke to that period in which it was first heard. The 80s proclaimed that ‘greed is good’. This song says it isn’t. It says it’s stupid.”

And we bought the record — I bought the record — and the “We Are the World,” and watched Live Aid and made donations. It was important, a rejoinder to Ronald Reagan and Maggie Thatcher, a way of acting without real commitment. Unlike the movement to divest from South Africa over its apartheid government, raising money for famine victims — a narrative that stripped them of agency and ignored Ethiopia’s political context — was easy. It allowed us — me — to pretend we were part of a larger movement that really did not exist.

Why does any of this matter today? Because of the remix release and because, as Adekeye Adebajo, then executive director of the Centre for Conflict Resolution, wrote in the Guardian:

“Three decades after Live Aid, it is clear that celebrity efforts to ‘save Africa’ have often done more to reinforce negative media stereotypes about the ‘dark continent’ and to portray its one billion citizens as helpless victims in a new ‘white man’s burden’”.

Or as Fuse ODG said more recently (quoted by Nels Abbey, in a Guardian op-ed):

“While they may generate sympathy and donations, they perpetuate damaging stereotypes that stifle Africa’s economic growth, tourism and investment, ultimately costing the continent trillions and destroying its dignity, pride and identity. By showcasing dehumanising imagery, these initiatives fuel pity rather than partnership, discouraging meaningful engagement.”

The song, as I wrote three years ago, is framed as “a demand that we wake up and do something,” while also presenting

the starving Africans as stock figures, presenting them in the same dehumanizing language used by the great English writers of the late-colonial period. It is a song that emphasizes difference, that underscores an us and them mindset. “There's a world outside your window,” the assembled vocalists proclaim, “And it's a world of dread and fear,” inviting the listening pity the poor folk from the “dark continent.” We can help them, the song says, though the reasons to do so are very much in keeping with Rudyard Kipling’s notion of “The White Man’s Burden” — that we have a responsibility, a burden, because we can and they cannot, because they are by nature, by place incapable.

Here is the full piece from 2021: