Monday Music: Bob Dylan on the Big Screen

The Film ‘A Complete Unknown’ Captures As Much of Dylan’s Genius As Any Film Can

Finally saw A Complete Unknown, the film version of Bob Dylan’s early years. I approached it with both anticipation and trepidation, as a long-time Dylan fan who has read dozens of books and articles on the folk bard (and written a few articles myself). I feared hagiography, or an unearned takedown, but what I think we get is a fair appraisal of Dylan the man and Dylan the artist at the moment he discovers his voice.

The film deserved all of its accolades — it was well acted, tightly structured and paced, and does a good job imagining that moment in Dylan’s life. Timothy Chalamet inhabits Dylan and his co-stars — Elle Fanning as Sylvia Russo (a fictional Suzy Rutolo), Monica Barbaro as Joan Baez, and Ed Norton as Pete Seeger — do the same for their characters. It doesn’t break new ground, or tell any new stories. And some will question the accuracy — and there are some liberties taken. But no more — and probably less than — most bio-picks, and I don’t think those criticisms are worth engaging with.

One of the film’s greatest strengths is that it doesn’t shy away from Dylan’s issues with women. While not physically abusive, his willingness to move back and forth between Russo and Baez and to use them — Russo introduces him initially to politics and art, and Baez gives him a more direct entree into the folk world — plays on their emotions, undermines them as individuals.

Dylan is a prickly character in the film, and apparently one in person — at least according to his biographers. His treatment of women in life and song is often brutal — Jody Rosen in the LA Times, in a review of Dylan’s book The Philosophy of Modern Song, describes his”mind” as “the storehouse for some extremely dark and disturbing ideas about — to use the retrograde term that Dylan himself employs — the opposite sex.”

This plays out in the film, with Russo and Baez never being central to the Dylan character. His expectation is that they are there for him, but there is never the sense that he is there for them and it is ultimately why Baez cuts ties with Dylan (for 10 years) and Russo walks away rather than live with the realization that she would be a priority in Dylan’s life.

Both actresses give powerful performances, imbuing their characters with a level of strength that allows them to stand as equals with Chalamet’s Dylan in the film.

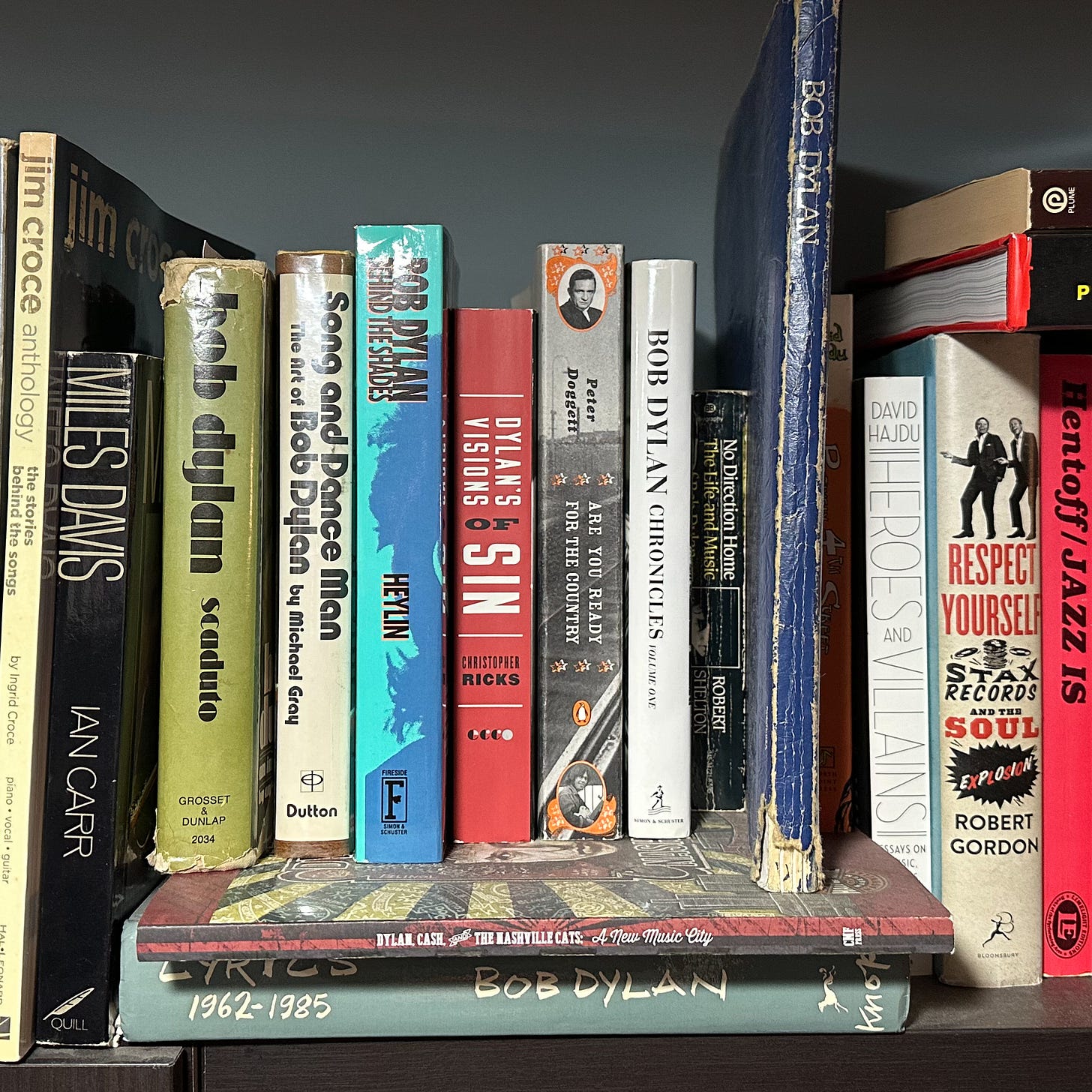

I’ve always viewed Dylan as a contrarian, as someone whose artistic choices are meant to confound expectations. Usually, it results in genius, but not always — the inconsistent quality of his music starting with Self Portrait is evidence that many choices have not been the right choices. Going electric — the climax of A Complete Unknown — is indicative of Dylan. It grew from his genius — the electric recording sessions that led to Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited in January and June were extensions and repudiations of his earlier work, extensions in that a song like “Corrina, Corrina” from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan features a full band and the album Another Side of Bob Dylan includes several songs that feel like they were written for a rock band and that would be covered by rock and pop musicians (see Song and Dance Man1). A repudiation because Dylan moved away from politics and the false purity of the folk movement to create something different.

A Complete Unknown captures this aspect of Dylan, even if it presents genius as a mythical quality and doesn’t fully offer a sense of the hard work that went into Dylan’s creative process. The movie’s focus is the debate over history and purity, and it draws its lines clearly with Dylan and Bob Neuwirth and some others on one side and an ambivalent Pete Seeger on the other side with the far more dogmatic Alan Lomax.

The film operates in extreme close-up. I’m not talking about the shots, but the focus. It bores in so narrowly on Dylan’s growth and the internecine debates in the folk world that it disconnects itself from the larger historical dramas that are swirling around. History makes its cameos — the Cuban Missile Crisis, and Kennedy’s assassination, and mention of Civill Rights — but only as brief mentions. This keeps the film focused on character, which is both a strength and a flaw.

Dylan’s transformation was both a personal seeking, not finding himself but inventing himself, creating himself as something new — as his character tells Russo. a way of defining himself out of almost nothing, but also a response to and part of the era’s shifting politics and social mores. Politics were a central part of 1960s culture and Dylan’s politics were decided left at the time (that would change later in life). But drugs and youth culture also were important, as were Dylan’s growing interest in literature, which gave him a new language and a store of new images to work with. The 1960s were not a decade of peace and love, but of revolutions and violence and his music began to reflect that.2

Lyrically, the electric albums of ‘65 and ‘66 were more allusive and surreal; musically, the albums captured the anarchy of the moment. The political turmoil — Kennedy’s assassination, the murder of Medgar Evers, Selma and Montgomery, Vietnam, the Harlem riots, the threat of nuclear war— made its way into Dylan’s music via the aural collision of grinding guitars and swirling organs, sheer volume and speed. The times were changing, rapidly, and in ways older audiences were struggling to understand.

Seeger, Lomax, and the folk purists — they were the older crowd. Seeger was 46. Lomax was 50. They were of a different generation and were still playing by the older rules. Dylan was 24 when he took the stage at Newport in 1965, was never a purist. He was inspired as much by Elvis Presley and The Beatles as he was by Woody Guthrie, was seemingly destined to go electric, though it. A Complete Unknown alludes to this but elides the influence of both on Dylan’s music — as Rafael Alvarez writes on Angelus. This is unfortunate, but the film still hints at Dylan’s love of rock a and roll and his connection to rock. The early scene, after Dylan first visits Guthrie in a New Jersey hospital, in Seeger’s car cannot be minimized. It is a statement of thematic concern, maybe even the thesis of the entire film.

Pete is driving. They are heading to Seeger’s upstate-New York house. Dylan asks if he can turn on the radio, fiddles with the dial, and settles upon Little Richard.

Alvarez describes the scene this way:

As the car pulls up to Seeger’s house in Beacon, New York, some 50 miles north of Greenwich Village, a snippet of Little Richard’s “Slippin’ & Slidin’” wails on the car radio.

Seeger disparages the song as nothing more than candy. In a quiet mumble, Dylan says he likes all kinds of music. It would have been a perfect moment, if just for another 30 seconds, to bring the King into the conversation. That would have fried Seeger’s banjo!

This is the debate that was taking place within the folk community. Seeger and Alan Lomax (played by Norbert Leo Butz) offer one point of view, one long discredited, that folk music represents something real, that authenticity also meant that white musicians were not real blues men (an argument that would be recycled in reverse later in rock history). Lomax, the collector, the musical anthropologist, represented the more extreme version of the argument. His defense in the film of the Newport Folk Festival as being about preservation sets him as backward looking, and out of step not just with Dylan but with others — including the folk musician Dave Von Ronk (played by Joe Tippet), who tells Dylan early in the film, “You can call it country or blues or rock'n'roll — we all keep rewriting the same song.”

Dylan would go on to write and rewrite, to tell his stories and retell others’ stories — and face plagiarism charges for it, despite it being a central way in which the folk music tradition (and so much rock and roll) has maintained itself.

We could say that Dylan proved to be bigger than folk music. Or maybe it is more accurate to say he inhabited and consumed folk. Like Whitman, he contained multitudes. A Complete Unknown captures a sliver of this, and it does it well. Asking it to do more would dilute its power.

Gray, Michael. Song and Dance Man: The Art of Bob Dylan, E.P.Dutton, 1972.

See my essay in Pop Matters, “Anarchy in the U.S.: Bob Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited,” 7 Feb. 2004, https://web.archive.org/web/20101112101407/http://www.popmatters.com/pm/review/dylanbob-highway61mft