Friday notes:

I don’t have a long essay today (well, I guess I do have one), but there are a number of important issues on which it is worth offering short comments:

1.

The United Auto Workers strike against the Big Three automakers is expanding today. As The New York Times reports, workers at two more factories have walked off the job in “the second escalation of strikes that started on Sept. 15 at three plants, one each owned by G.M., Ford and Stellantis, the parent of Chrysler, Jeep and Ram.”

Luis Feliz Leon, who has done the best job on the strike (for Labor Notes and In These Times), writes that the that the Stellantis was spared the strike expansion this week because it has the car company has been cooperative.

According to UAW President Shawn Fain, Stellantis made “significant progress” on cost-of-living allowances, the right not to cross a picket line, and the right to strike over product commitments and plant closures. “We are excited about this momentum at Stellantis and hope it continues,” Fain said.

Stellantis is not out of the woods, of course. If progress is not made, it is likely they could be targeted in the next strike expansion. At the same time, the UAW is going to take a more creative tack. Leon writes that

The UAW is now calling on community supporters to organize small teams to canvass dealerships that sell and repair Big Three cars and trucks. On Tuesday, the union issued a canvassing tool kit with instructions, flyers, press releases and talking points.

Much of the mainstream press has focused on the impact on the economy — while also creating a false equivalency on labor issues between Joe Biden and Donald Trump, the likely nominees for president for the two parties next year. Biden visited the picket lines and walked with workers — said to be the first time a sitting president did so — while Trump spoke at a non-union parts plant, calling on its employees to tell their “leader” to endorse Trump. The “leader,” one assumes, was Fain, president of a union that did not represent workers at the plant.

Biden’s labor record is mixed — much of his efforts have been positive, but they were badly undercut by his interference in the rail workers’ contract battle on the side of the rail companies, and it is worth debating just how good he has been on labor issues. Still, it is hard to argue that he has been better than most presidents on labor, and a 180-degree turnaround from Trump, who appointed a slate of decidedly anti-worker members to the National Labor Relations Board while railing against — but doing next to nothing to address the damage being done to workers around the globe by corporate greed and its desired to pit workers against each other in a race to the bottom on wages.

2.

The UAW strike is part of a larger labor moment. The Writers Guild is settling, winning what it is calling “guardrails” against the use of artificial intelligence and changes in pay related to the changing ways television and film are producing content.

3.

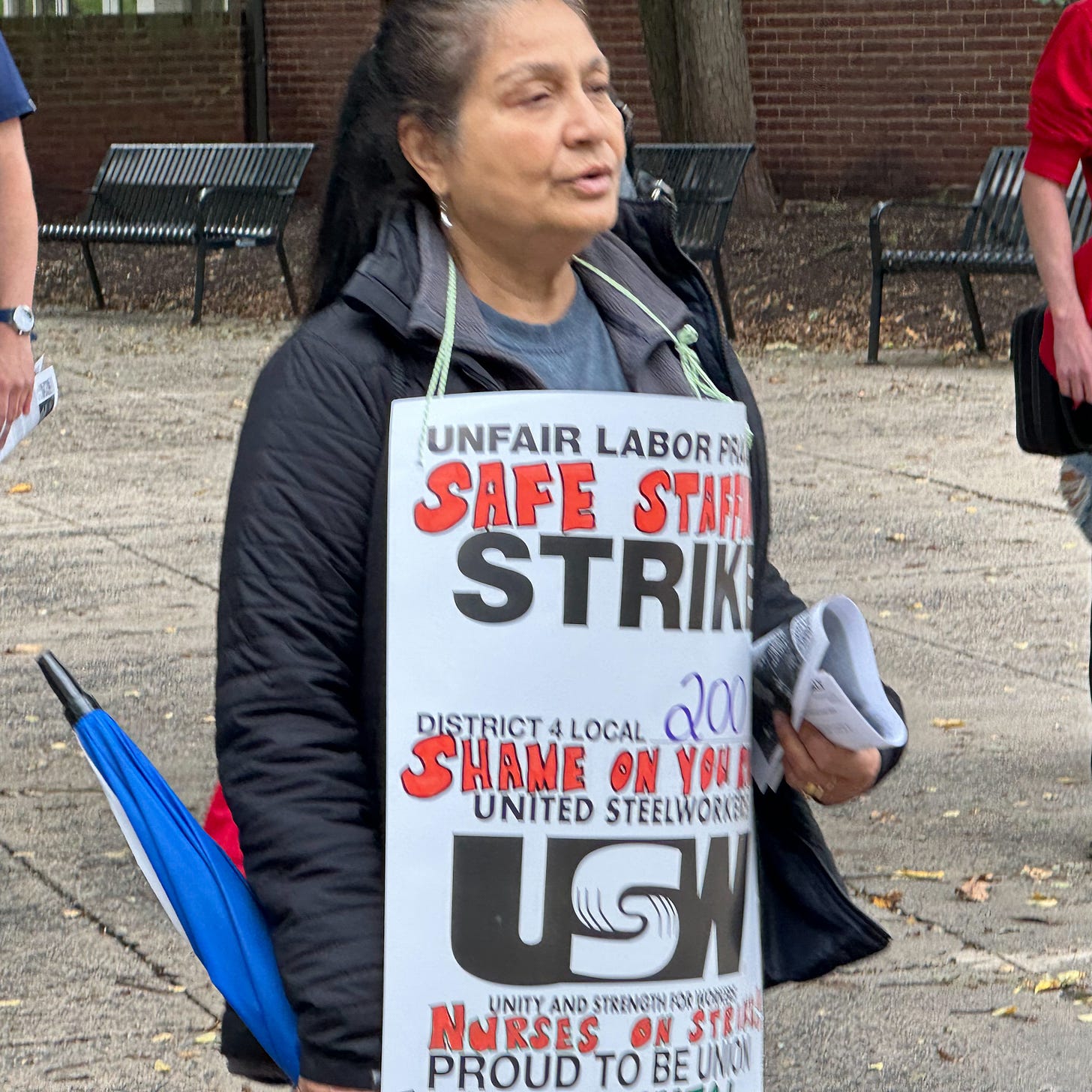

Nurses at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital in New Brunswick remain on strike, though an injunction issued by the state Superior Court has constrained the union’s ability to organize rallies and protests in front of the hospital.

According to the New Jersey Monitor, Superior Court Judge Thomas Daniel McCloskey, sitting in New Brunswick, ordered “to stop disruptive picketing, calling their round-the-clock protests since their walkout started Aug. 4 ‘unlawful acts.’”

The judge said that

the defendants’ conduct interferes with essential emergency and scheduled medical services normally provided by the hospital and that the welfare of the community, patients of the plaintiff’s hospital, patient families attempting to gain ingress and egress from the hospital to be and visit with patients under the care of the hospital, treating physicians and medical and administrative support staff providing such patient care, and of the general public as a whole is being adversely affected by such conduct.

Nurse Judy Danella, president of United Steelworkers Local 4-200, called the order “an anti-union, union-busting tactic on their end.” Picketers, she told the Monitor, had not interfered with the safety of patients.

“We have the right to freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, but they’re saying we were blocking things. Nobody’s been hurt. Every time there was an ambulance, they did stop to let the ambulance through. It’s very fabricated,” Danella said.

On Thursday, members of the Rutgers faculty unions hosted striking nurses at a picket at Voorhees Mall on College Avenue. The nurses I talked with view hospital management as more concerned with generating profit than with providing care. The New Brunswick hospitals — the main unit and trauma center, the children’s hospital, a cancer institute and numerous other specialty units — are part of RWJBarnabas Health, the state’s “largest integrated health care delivery system.” The complex is the flagship of a system that serves about 3 million patients a year, who rely on top-quality nurses.

The issue, the nurses say1, is that the hospital is ignoring safe-staffing recommendations as suggestions and not as a critical component of quality care that are supported by peer-reviewed studies. Numbers vary by department and are affected by the needs of patients, nurses say, with the sickest patients sometimes needing two dedicated nurses.

“Safe-staffing ratios are not something we came up with,” said Carol Tanzi, an organizing leader for the nurses. “These are generally accepted based on the type of patients. So it's not that we're asking for something so outrageous. It’s kind of what the gold standard is.” The hospital, she says, wants people to think of safe-staffing rules as “a foreign concept.”

“They keep calling them guidelines, which are not enforceable, meaning if the wind changes, they'll say, ‘oh, we can't can't provide that for you today,’” she said.

Right now, nurses say, hospital administration wants to address shortages with overtime or by shifting nurses from unit to unit, which is not sustainable and creates what Medical ICU nurse Aaron Habrack says is an unnecessary and dangerous triaging of patients. In the MICU, he said, there should be no more than two patients per nurse, though it might be one to one with some patients — those on ventilators or dialysis — or even two nurses to a patient. Under the current system at RWJ, he said, MICU nurses often “triple,” or are given a third patient because of a shortage of staff. That strains the ability of nurses to give their patients the proper attention.

“When I have my two patients, the way our unit is set up, I can actually sit at my desk and there's windows into the patient's rooms. And I can have a visual on both of my patients, I can see and hear in the rooms at all times while I'm working,” he said. “If they give a third patient to me, now I have a third patient that is removed from my desk that I'm not able to give that consistent monitoring to, so I’m constantly back and forth,” which means there are moments when each patient is not directly monitored.

“We do like a lot of teamwork, where we're all kind of helping each other out, but we do have our primary responsibility to our own patients,” he said. “We're always ready to jump in and assist each other when somebody has more patients than they should safely have or has an especially sick patient, but that kind of takes them out of that team dynamic and hurts the whole team.

“If I hear an alarm going off a couple rooms away, he said, “I don't feel comfortable leaving my three patients to go check on someone else, because there's no one to watch my three people.”

That, he said, “creates an environment where we start to have to prioritize tasks that should not need to be put into triage, (choosing) between if I hear a ventilator alarm and an IV pump alarm, now I have to think in my head ‘what could that be going off and is that more important than attending to this ventilator in the room. It becomes a much more demanding mental stack to balance when I have more patients than what I should safely be allowed within our guidelines.”

This is a battle between the power of labor, of workers, and the power of management. Like our strike in the spring (the faculty strike at Rutgers) and the strike by UAW workers, the stakes are not just local. What happens in New Brunswick will matter for the rest of the state. Nurses at other RWJBarnabas units are watching — the same way that other colleges and universities were watching when our unions walked in April. Our wins at the bargaining table, which were driven by our militancy, are being used as the model for other schools. RWJ nurses find themselves in the position, fighting in the same battle. They deserve our support.

Comments from Carol Tanzi and Aaron Habrack were from interviews I conducted during the Thursday protest. I talked with numerous nurses that day and in weeks past for a story that will appear in The Progressive.