(The following essay was triggered by an ad in the recent Harper’s magazine for a documentary on artist Lynd Ward. I had not heard of him but was intrigued and “read” God’s Man.)

*

The story is Faustian. The young artist making a deal with a shadowy presence. A masked and top-hatted man who will give him a brush with supernatural powers that will raise him from obscurity to fame. There will be costs that make happiness impossible. That doom him in the end.

It’s a tale oft told. Ambition and greed. Nothing surprising. It’s the way the story is told. In stark black and white. Without words. Image after image. More than 130 in sequence that composes the wordless novel God’s Man.

Art Spiegelman, the dean of graphic storytelling, described Lynd Ward as an influential progenitor of the graphic novel. His woodcut narratives violated a Western artistic norm that separated visual and written media.

“Western culture, Spiegelman writes,

was admonished against confusing between the nature of poetry or prose—written forms whose province is time, and the nature of visual forms like painting and sculpture, whose province is spatial.

The comic, which had grown in popularity in Sunday newspapers, was seen as low-brow. Unworthy of intellectual consideration. We still hear this. Still have cultural gatekeepers who see comics, graphic novels, superhero stories, as childish. That these stories often offer the most complex comments on some of our most thorny issues — immigration, the use of violence, the transparency of policing — is no matter. The old divide between low and high and the old taboo against mixing media still holds for some.

But the best graphic stories are high art. Spiegelman’s Maus tells the story of his family and the Holocaust. Alison Bechdel offers a meditation on family. Marjane Satrapi’s Persephone is about the Iranian Revolution. Solomon J. Brager — whose new book Heavyweight tells his own family story and meditates on identity and the wreckage of colonialism — told my students recently that graphic nonfiction requires a level of attention, research, and fact-checking equal to any news report or academic study.

Graphic storytelling is also about perspective. About the eye and what the eye sees. The artist-reporter has to be present, which makes it more like the best magazine writing and less like newspapers.

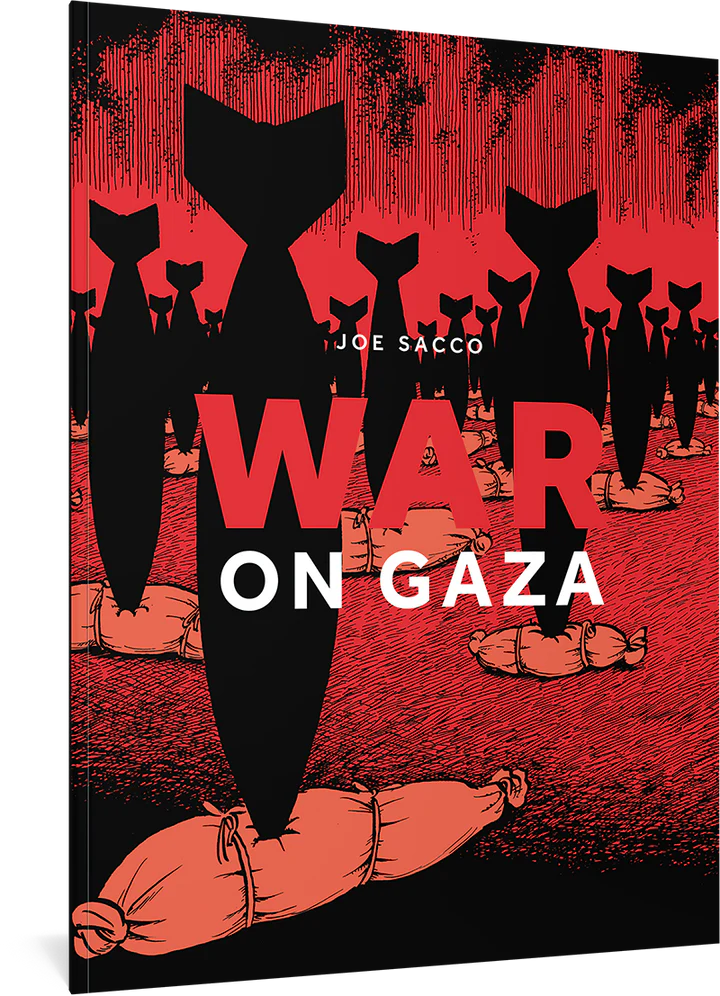

Sacco’s new book, War on Gaza, is as much essay as nonfiction. Nightmarish and surreal. A response to the limitations placed on journalists and the genocidal violence being inflicted by Israel on Gaza and its residents. "Israel has not allowed any foreign journalists into Gaza,” he tells Haaretz. This made reporting impossible.

"My only alternative was to turn to the essay format and to reach back to my satirical roots and approach the war from that corner. Gaza has been turned into a hell, yes, so if my comics reflect that in some small, abstract way – good.”

He calls it an “essay format,” but that’s not really accurate. The graphic format’s use of image and layout allows the artist-reporter to place the reader in physical space in a way essayists can only strive to do. The ability to manipulate space and time in storytelling is the medium’s greatest strength.

“Nothing,” Spiegelman writes, “could violate this long-held aesthetic taboo (of keeping visual and written word apart) more directly than comics, a kind of picture-writing—the very layout of a comics artist’s page insists on pulling the reader from one drawing to the next.”

Ward does this without words. Uses the images alone to create impressions. Associations. He presents the city as corrupt and the country as wholesome, an unfortunate vestige of earlier American themes. The novel is a criticism of urban capitalism. And the choices made are the choices of capitalism — money, fame — and they ultimately determine all that follow.

Ward’s wood-cut drawings are detailed but still archetypical. Dialectical. In theme and imagery, God’s Man is a product of its time. Published in 1930 as a world-wide economic depression was taking hold. It’s an example of the kind of socialist and Marxist art prevalent when Ward was active. Cut in broad strokes. Almost utilitarian. It presents the attractions of quick success — of capitalism — as a threat to what makes us human. It’s a system that does violence to the soul, as the nameless protagonist learns.

It’s an argument our of fashion today in our consumer-driven economy, but that still holds. American capitalism continues to distort our choices, weakens our connections, creates division and demands scapegoats. Capitalism is about power and profit, and most of us are left to scratch to get by.