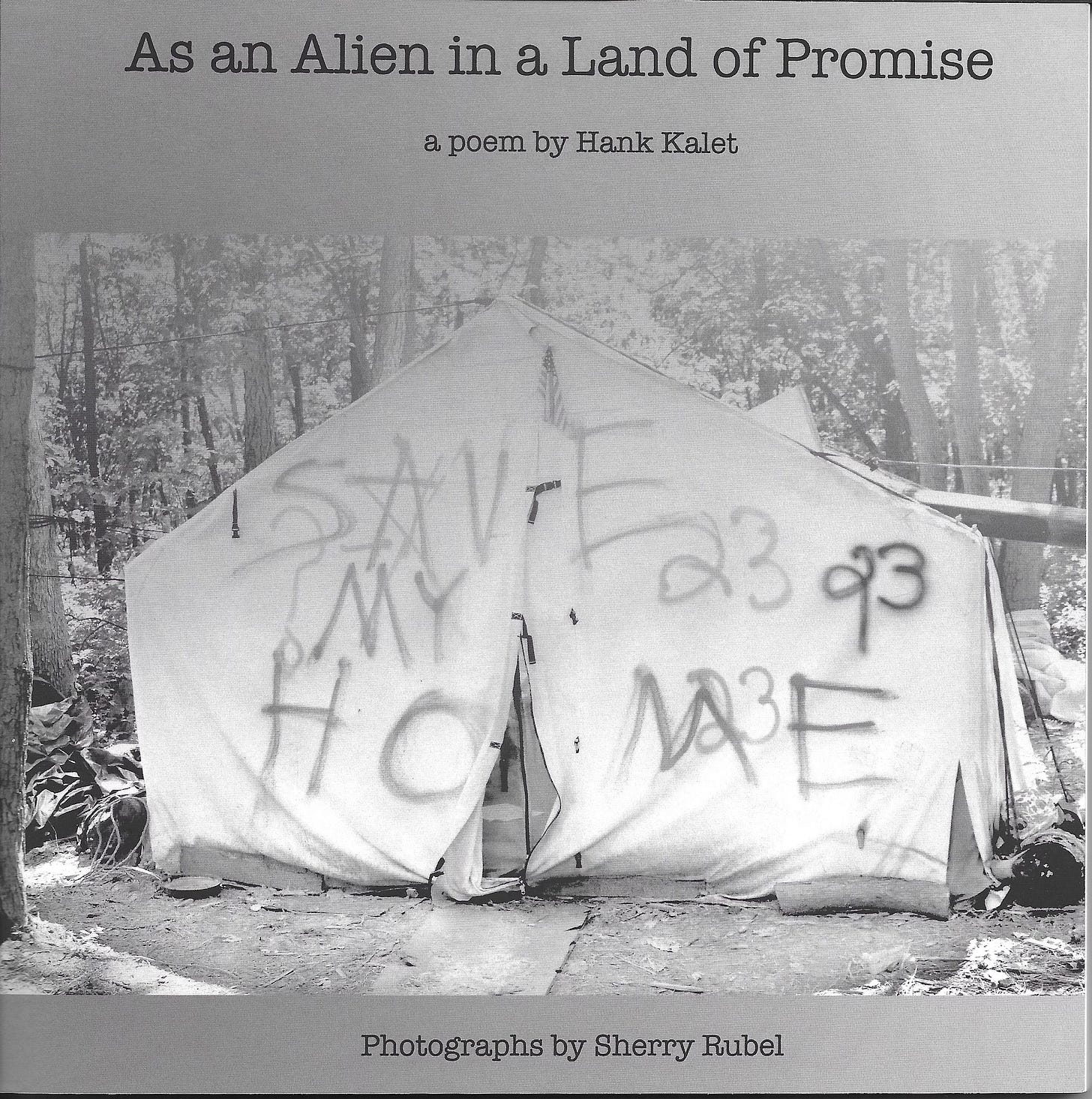

Out of the Shadows

Suburban Poverty Exists and Is Part of a Broader Crisis of Capitalism and Work

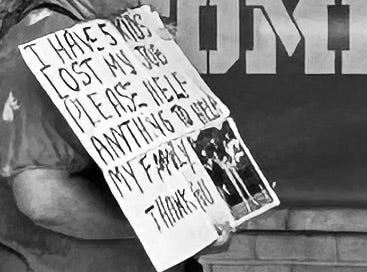

There was a woman standing by the entrance and exit doors of the Pennsylvania Dutch market on Saturday, the Amish. She was middle aged, probably in her 40s, possibly Latino, but I couldn’t tell. She held a sign that said she lost her job, that she had five kids, and that asked for help.

The market is on Route 27, on the order between Franklin and South Brunswick townships and only a mile or two from Princeton. It is a relatively affluent area, even when compared to the rest of New Jersey. Ranch houses now go for half a million dollars, and many houses sell for more than a million.

So, the sight of a woman so blatantly asking for hand outs might seem unusual, might even raise suspicions. Some will see her as a scammer, as pretending at poverty to put one over on unsuspecting mopes like me. I was embarrassed that I had no cash and could only manage to gave her $4.50 in change I had in my car.

She thanked me, but didn’t want to talk. I always ask when I can — I’m a journalist, after all and the existence of men and women like her is a story that needs telling.

Some open up, but many don’t. One Marine vet I met on a New York street told me he appreciated when people stopped, because it meant they saw him as human, as a real person. I always keep that in mind.

I also get why some would be suspicious, especially in suburban settings, though the scam factor seems small; why would someone stand in the heat — or snow and rain — to beg for money if they didn’t need it? There are more lucrative scams available.

Some of the suspicion also stems from an assumption that poverty is mostly confined to urban areas or deeply rural ones. Suburbia is exempt, the thinking goes, except it’s not. Suburban poverty exists in shadows.

An Institute for Research on Poverty at University of Wisconsin fact sheet on suburban poverty, over “the last 20 years, the geography of American poverty has shifted, with

an increasing number of America’s poor people now living in suburbs.” Half of recent growth in poverty occurred in the suburbs, with current reports showing that there are “roughly 3 million more poor people in suburbs than in cities.”

This matches my experiences as a reporter covering mostly suburban communities in Central Jersey. Every town had at least one food pantry, and every one was relatively busy, though it fluctuated with shifts in the larger economy. Few pantry clients are interested in talking with reporters, even off the record. The suburban poor seek anonymity, seek to avoid the gaze of critical neighbors, of deeply embedded Puritan beliefs that prosperity God-given and poverty proof that the poor were not blessed.

It is not a divinity that creates prosperity or poverty. Rather, it is a different kind of “god” that intervenes, a god we call the market, capitalism. The market dictates all, assigns value or withholds it, determines what is a public and private good and what is not. Capitalism’s focus on economic efficiency, on streamlining, cutting costs to boost profits, has eroded the public safety net.

This will get worse with Donald Trump back in the White House, especially if there is a Republican majority in both houses of Congress.

Democrats, though, are only nominally better. The party — with exceptions — is committed to market capitalism, though with the human face of regulation.

The Biden administration has offered some useful anti-poverty programs, but they face an array of hurdles and are probably too small to address the systemic issues that create a backed-in underclass. What we need are stronger labor protections and empowered unions, some kind of universal income, Medicare for All, and an end to a system that privatizes gains and socializes losses.

In the meantime, our underfunded networks of food banks and soup kitchens will need our help, as will individuals in financial straits.