Monday Music: Dylan's Anthem for Israel

'Neighborhood Bully,' from Infidels, Could Have Been Written by Netanyahu

Supporters of Israel continue to argue that it the Jewish state is fighting a defensive war. It is a claim, as Gideon Levy points out, that supporters have long pressed, and that is based on a “self-victimization (Israel) so very much enjoys.”

He was writing this in the wake of what he described as an “ugly, criminal pogrom against Israeli soccer fans took place in Amsterdam on Thursday,” an event that was reported without context by an Israeli media that “set another record for the incitement, exaggeration, fearmongering and, above all, the concealment of information that doesn't fit the narrative.”

He could be talking about the American media, too, and many in the American Jewish community, which viewed the events in Amsterdam through the lens of the Holocaust, even as it has become clear that an alternative set of facts needs to be centered.

Levy, whose new book The Killing of Gaza I plan to review in a coming post, reminds us that the Amsterdam “pogrom” was preceded by some “Israeli fans rampag(ing) in the streets,” shouting “disgusting … chants of "We'll screw the Arabs" (in Hebrew) and the removal of a Palestinian flag legitimately hanging from the balcony of a building.” These events, he points out, “were almost never shown in the Israeli media,” because they “could spoil the image of antisemitism.”

“No one,” he adds, “asked the first question that the sight of the violence and hatred in Amsterdam should have raised: Why do they hate us so much? No, it's not because we are Jews.” He is not arguing that there was no antisemitism at play, only that “the attempt to pin everything on it is ridiculous and mendacious.”

(T)he Amsterdam riots also have a context, and Israel is unwilling to address it. It would rather send a bodyguard with every Israeli soccer fan who travels to Europe from now on than to ask why it is that they hate us so much and how this hatred can be quelled. After all, it did not erupt like this before the war in Gaza.

That the war on Gaza is central to understanding what happened in Amsterdam should be obvious, but we have been told for too long that Jewish victimhood obviates the need to think about anything beyond antisemitism. In this way, it is consistent with the larger effort to erase the Palestinian people and the suffering they’ve endured for going on a century.

Levy’s column had me thinking of Bob Dylan’s “Neighborhood Bully,” from Infidels. The song, like so many of the arguments being made by supporters of Israel, conflates Israel with Jews and criticism of Israel with antisemitism., and offers an intersection of the Israeli victim narrative, an American movie western sensibility, and Dylan’s own apocalyptic vision. It is a song that stirs together the details of historical antisemitism, contemporary (i.e., early 1980s) Israeli history, a cowboy-like figure that stands in for Israel, and end-time eschatology over one of Dylan’s harder rocking musical performances.

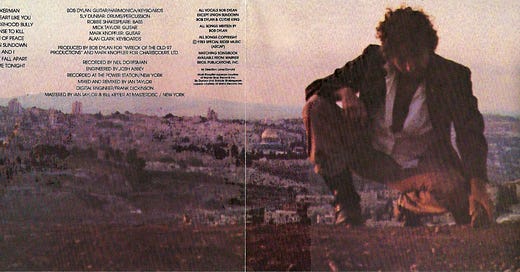

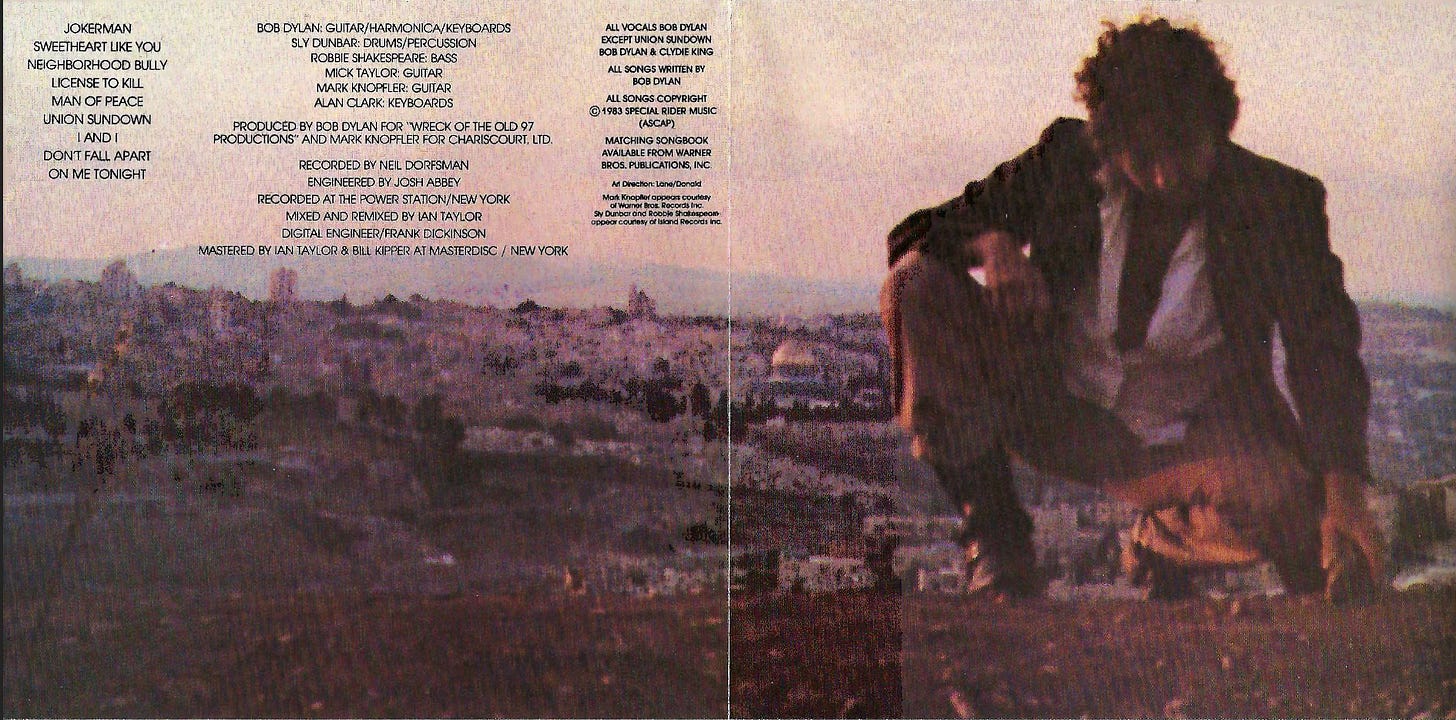

Infidels is a flawed album typical of his 1980s output. Still, it was received (rightly) as a sort of comeback. Some of the music holds up well — “I and I,” for instance — while some are held back by the prejudices and sexism of its time.

The album received mixed reviews, but most of the critics described is as a return to topical writing. Some critics did question the politics, but not as many as one might think. (A 21-year-old Hank didn’t question, either.) The album, therefore, was linked to his earlier and periodic returns to topical music. “Neighborhood Bully,” however, is far different from his Sixties’ political songs — and from the over political statements he would make on Desire or even Street-Legal, because it overtly endorses political violence and elides the reality of Israel’s long-term occupation, which was most apparent in the massacres in Lebanon. “Neighborhood Bully” stands out both because of what it doesn’t say and because of what it does say, and the Zionist political space it opts to occupy.

Dylan’s “bully” — his use of the word is ironic — is Israel; the enemies, while not named, are the Arab world writ large and presented as a single force, erasing Palestinians as a people. The enemy “say he’s on their land” and have him “outnumbered about a million to one.”

Dylan disputes any attempt to literalize the song. He told Kurt Loder in 1983 that he was “not a political songwriter.” He was responding to a question about “Neighborhood Bully,” a song on Dylan’s Infidels that pretty clearly takes a rightwing Zionist line. “Neighborhood Bully,” he said, “is not a political song, because if it were, it would fall into a certain political party.”

This is nonsense, of course. “Neighborhood Bully” is a political song, a problematic defense of Israel that ignores the Israeli massacre at two Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon and what was, at the time, a 26-year occupation of Gaza and the West Bank (and the brutality inflicted on Palestinians by Israelis since before independence).

Dylan, I assume knew this, even as his answers are consistent with his unwillingness to be pinned down by interviewers. He has rarely chosen to offer straight answers, and has preferred to remain cryptic. Dylan tells Loder that, “just because somebody feels a certain way, you can't come around and stick some political-party slogan on it.

If you listen closely, it really could be about other things. It's simple and easy to define it, so you got it pegged, and you can deal with it in that certain kinda way. However, I wouldn't do that. 'Cause I don't know what the politics of Israel is. I just don't know.

At best, that answer is a cop-out — and at worst it is a lie. Israel’s politics are all over the song, from its pushing of the victim card, to its refusal to see Palestinians as an occupied people or a people worth respecting.

This is not conjecture or some kind of English-Major analysis. It is there in the lyrics of a song that, despite hiding its thematic concerns behind the allegorical construct of the maligned “bully,” are right there on the surface.

Dylan — like Jack Kerouac and much of American culture in the pre- and post-WWII era — was swept up by the mythology of the west, with its extreme version of individualism and absolute moral clarity. There were good guys and bad guys, white hats and black hats, and the white hats stood for a kind of status quo version of the law and — a key point — a defense of the colonial imperative. The push west was part of an American political crusade that privileged white settlers and cast others — African slaves, natives — as lesser or inconvenient.

You can see the colonialist myth at work in “Neighborhood Bully” in the verses that buy into the false narrative that Palestine was a land without a people, or a land of people who were incapable of seeing the potential of the land. The Palestinian Arab, the myth says, were primitives — echoing the presentation in American film of the American Indian as savage.

So, when Dylan sings, “He's made a garden of paradise in the desert sand / In bed with nobody, under no one's command,” I flash back to Leon Uris’ Exodus, an awful piece of propaganda posing as a novel that helped spread this myth in the United States. Uris’s book came out in the late 1950s — was made into a film starring Paul Newman in the early 1960s — and, for all appearances, is no longer read, but its underlying colonialist argument still animates Israel’s expansionist efforts and much American support for the Jewish state in the United States. The book was about the birth of Israel, but Uris engages the western myth and the racist caricature of Palestinians and Arabs he provides are totally consistent with movie westerns.

Dylan does something similar in “Neighborhood Bully,” presenting his “bully — Israel — as a kind of anti-hero cowboy, as a character who “just lives to survive” and has been “driven out of every land” (a nod to Jewish exile and the diaspora). Despite being the outsider, the “exiled man” who is “hounded and torn,” and “always on trial for just being born,” he has justice at his back and it gives him a kind of moral power that allows him to live outside of the law.

Well, the chances are against it, and the odds are slim That he'll live by the rules that the world makes for him 'Cause there's a noose at his neck and a gun at his back And a license to kill him is given out to every maniac

The speaker/singer — Dylan, if you will — merges two images: Cowboy and persecuted Jew, affixing movie-western images of noose and Lynch mob and isolation and in the process creating a character we are supposed to support and forgive, “because he lives to survive.”

The bully is the underdog. He is righteous and his turn to violence is equally righteous. “He’s not supposed to fight back, he’s supposed to have thick skin / He’s supposed to lay down and die when his door is kicked in.”

Some — like the author Jeff Taylor — see Dylan as being disconnected from contemporary politics, especially from Israeli politics, and “more to do with the future Battle of Armageddon.” While Dylan may not be — or have been when he wrote “Neighborhood Bully” — a political Zionist on a personal level, this song is an anthem of political Zionism that fits neatly within Dylan’s rightward shift.

Listening today, as Israel wages a vicious war on Gaza that targets civilians, a war Israel is justifying by the horrific murder by Hamas of 1,200 Israelis, I hear the arguments being made by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu or some of the more bellicose supporters of Israel in the United States.

Probably both. He’s never fully abandoned these impulses. His lyrics have remained apocalyptic over the last 40 years.

It’s interesting to think about whether this is leftover Born Again apocalypticism (is that a word) or a misguided way to return to

his Jewishness.