In Odessa, they brace for attack. Create aid stations from nothing. “(F)ill sandbags in preparation.”

The Russian army shells towns to the north. Continues its move west and south. One man shows a photo to a CNN reporter. Image of the city during World War II. We fight again, he says. Fight the Nazis. The Soviets. Putin more than once.

Odessans prepare with sandbags. Join in a human chain to fill and pass the bags to trucks that will bring them to the center of Ukraine’s third-largest city. “We will defend our city and our country, for sure,” says another man.

I think of borscht. Of my grandfather eating borscht with boiled potatoes. Rye bread with butter. Sipping a beer. He was from Ternopil. A Polish Jew. Ternopil is now in Ukraine, to the west. Was part of Poland until partition re-placed it in Austria. Then in Russia and the Soviet Union. His father’s naturalization in the early 1920s says they were from the kingdom of Austria.

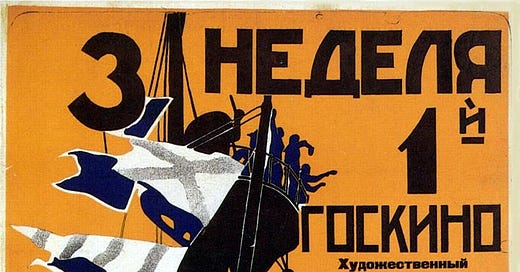

I think of borscht, not just because of him or even my dad. I think of borscht because of Battleship Potemkin. “For a spoonful of borscht,” is the rallying cry of the Bolshevik rebels, of the lower-ranking sailors and workers in Odessa, in Ukraine. Battleship Potemkin is a Soviet-era masterpiece, directed by Sergei Eisenstein and released in 1925. Part film experiment — it gave the world “montage” as a film technique, or the colliding of images to create meanings — and part agitprop, it tells the story of a 1905 mutiny that enflames the already brewing Russian civil war. The film opens aboard the title ship as the sailors Matyushenko and Vakulinchuk discuss the brewing revolution and whether the crew should join with the rebelling workers, and then proceeds through a template of abuses by Tsarist forces as represented by the officer corps and later by the Tsar’s forces themselves. The people are massacred and the battleship, now in the hands of proletarian sailors, prepares to defend the workers of Odessa, of the Ukraine, from imperial onslaught. The sailors’ bravery inspires the onrushing Tsarist warships to stand down, presumably because the prols on board have joined the larger revolution.

Eisenstein was a Soviet communist, and was not focused on the Ukraine-Russia dynamic. His target was the imperial power structure and the depredations of capitalism. The stale bread. The maggot-infested meat. The thin borscht. The maltreatment based on class and rank. He kept his focus narrowly on the dialectical power split between capital (in the guise of the military and monarchical power structure) and the workers. His presentation is either/or, one side or the other, without nuance.

Still, the film feels fresh because of its technical innovations, and because history seems to be repeating itself in Ukraine today as Russian forces move deeper into Ukraine and the news reports of resistance in Odessa, where much of the film takes place. As I watched Battleship Potemkin for the first time since graduate school (and probably the first time all the way through in this format), it is difficult not to see Putin as Tsar Nicholas II, who was in power during the Russian revolution, an autocrat insulated from dissenting voices, and the Russian army as the cossacks and soldiers that opened fire during the Odessa steps sequence.

The 11-minute sequence, one of the most famous in film, is hard to watch. Bodies fall. Men, women, children. Men who have lost limbs to Russia’s most recent war with Japan are forced to flee, to essentially hop in retreat down the steps, but to no avail. The bodies drop, and it is only the transition to the final sequence, “One Against All,” that brings this massacre to an end and forces a change of tone in the film as the rebel sailors aboard Potemkin ready for battle with the Tsarist armada, the fleet preparing to take out the Potemkin and crush Odessa and extinguish any ember of rebellion that might remain.

As the Potemkin sailors prepare for almost certain death, the armada sails closer and closer until, to the shock of the rebels, the armada sailors are putting down their arms, refusing to fight, to target their fellow workers. It is a moment of victory, of glory, a story being told at a propitious moment in Russian history, shortly after Lenin’s death but before the consolidation of power by Stalin.

The film, as I said, sets up a simplistic dichotomy, a good (workers, low-rank sailors, pensioners) and evil (Tsarist power). And it resolves this dichotomy by placing a thumb on the scales of the workers, endorsing a message of class unity.

In Odessa today, according to a story in The Washington Post, residents seem resolute.

“The greeting, ‘Glory to Ukraine,’ has become the most common in Ukraine,” said Alexander Slavskiy, who headed a government fund 10 days ago but is now a soldier with the area’s Territorial Defense. “Before this, it wasn’t like that. The city is mobilizing. Everyone who wanted to leave, evacuated, but so many people stayed.”

And, perhaps just as significantly, a vocal minority of Russians are taking to the street to demand an end to the invasion, which raises at least some hope that a Battleship Potemkin kind of ending could happen.