I’m having trouble breathing. For the last five months, I have struggled with a persistent cough that has gotten worse even as treatments for a sinus infection and bronchitis appear to have done what they were supposed to do.

Apparently, my breathing struggles are part of a longer-term issue with my lungs that I did not know about and that, according to my pulmonologist, does not match my medical history.

I am explaining this not to elicit sympathy. My struggles are my own and, while difficult, they appear manageable. But they have slowed me down and have redirected my attention. Political concerns, the theme of this Substack, have been taking a backseat to doctor’s appointments and questions about my own mortality, and my reading has shifted to books on existential philosophy, Zen Buddhism, and Judaism.

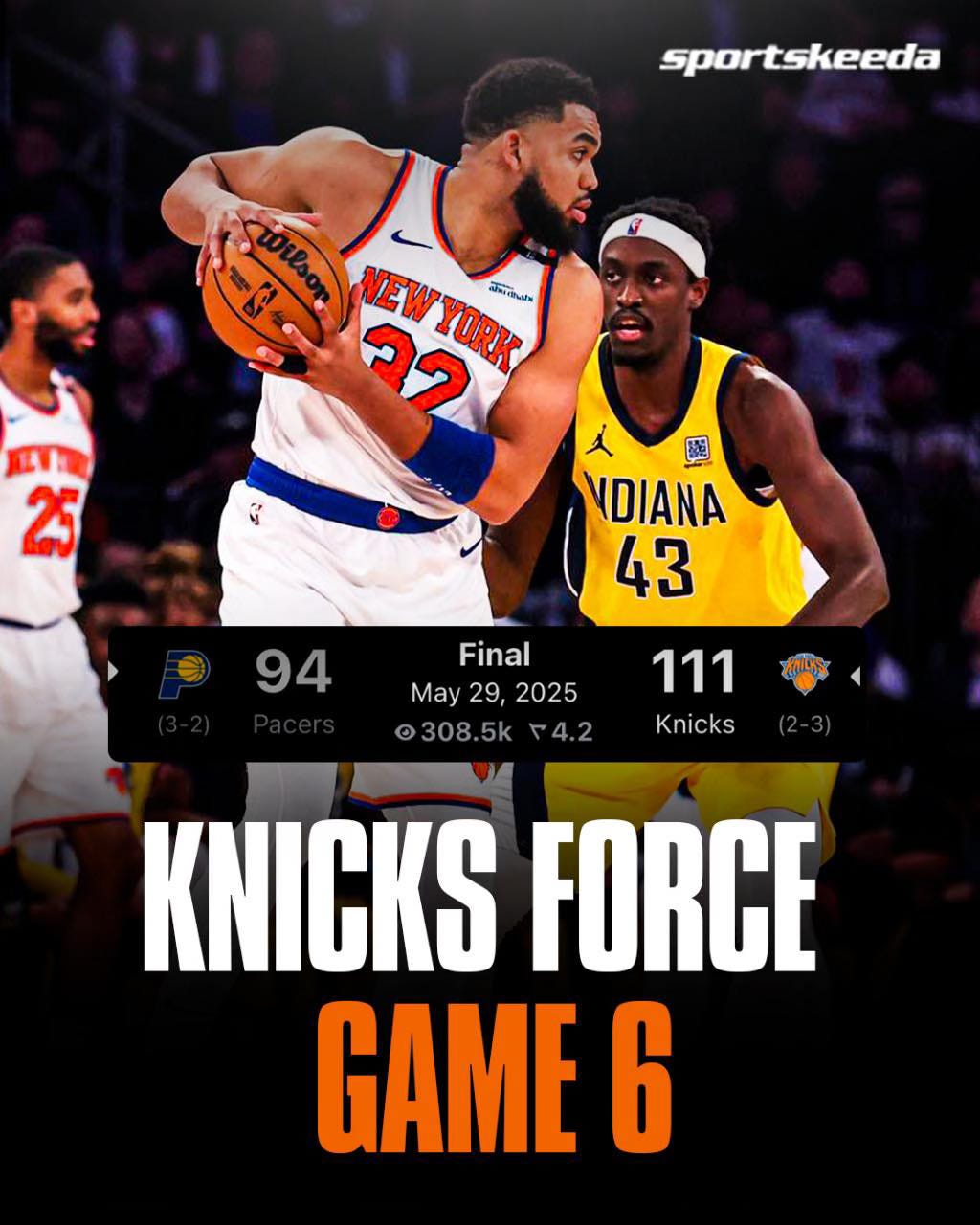

And, as I’ve done since childhood, I’ve lost myself in sports, in the roller coaster that has been the Knicks’ playoff run and the early successes and shortcomings of the Mets this season. I get that these may seem like “bread and circuses,” the kind of diversion the power structure relies on to keep us fat and happy as they pick our pockets and seek to enhance and make permanent their power.

The Knicks won last night when they were supposed to give up and go home — and, perhaps, there is a lesson in their effort and success. They are not out of the woods — down 3-2, they have no margin for error if they are to get to the NBA Finals for the first time since losing to the Spurs in 1999 — but they have life and hope and that is important.

We have life, as well. Even as President Donald Trump engages in what Marc Cooper described today as “Then Unified Field Theory of Madness.” Even as the Trump continues to demonize immigrants, to round them up and ship them out (though not at the pace he promised, thankfully). Even as the administration guts regulations that were enacted to protect Americans from polluted air and water and other ravages caused by capital’s disdain for the public. Even as he threatens higher education and seeks to remake it into a sycophantic tool to groom apparatchiks, even as he threatens the lives and livelihoods of transgender and non-binary individuals.

We have life and hope and that is what is important. This is what Rebecca Solnit means when she describes being hopeful, but not optimistic, not assuming that “everything was, is or will be fine,” but working to make our hopes, our goals real. Hope is about possibility, and possibility is something that can sustain us.

“Your opponents,” she wrote in 2016 as Trump was chasing his first term in office, “would love you to believe that it’s hopeless, that you have no power, that there’s no reason to act, that you can’t win.” They want to beat you — us — down, erase the word “possible” from our vocabulary. But: “Hope is a gift you don’t have to surrender, a power you don’t have to throw away.”

Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act. When you recognise uncertainty, you recognise that you may be able to influence the outcomes – you alone or you in concert with a few dozen or several million others. Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists. Optimists think it will all be fine without our involvement; pessimists adopt the opposite position; both excuse themselves from acting. It is the belief that what we do matters even though how and when it may matter, who and what it may impact, are not things we can know beforehand. We may not, in fact, know them afterwards either, but they matter all the same, and history is full of people whose influence was most powerful after they were gone.

I am trying to take this to heart as I struggle with my ailment — bronchiectasis — and as we, as a nation, as a democracy, struggle against the Trump agenda.

Each of us has the power to resist what is happening. We may not see that, may feel an impending sense of doom — an acceptable response, of course, because we have allowed our democracy to atrophy by opting out, by ceding our power to “saviors.” Trump is only the latest, on the right, but Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, Joe Biden and others have served this purpose on the left. We expect others to fix things, when we should be listening to Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez who are imploring Americans to stand up for themselves, to get involved, to fight back.

Do not expect the courts to save us, and not just because a majority of federal judges have been appointed by Republicans. The courts’ power is the written word, its rulings, but what happens when Trump decides to ignore the courts, to ignore even Congress?

Trump and Trumpism are not normal. We cannot rely on normal checks and balances to slow or stop its spread.

We cannot let it get to that point. We need to stand up for the most vulnerable — immigrants and students, workers, the poor and homeless, minorities, women, and the LGBTQ+ community.

Each of us needs to look inward and ask ourselves what we can do. For me, it is union work and my writing. And, if my health allows, I will hit the streets.

As Solnit writes, when the public awakens, “we are no longer only the public: we are civil society, the superpower whose nonviolent means are sometimes, for a shining moment, more powerful than violence, more powerful than regimes and armies. We write history with our feet and with our presence and our collective voice and vision.”

The mainstream media may dismiss this, but

Together we are very powerful, and we have a seldom-told, seldom-remembered history of victories and transformations that can give us confidence that, yes, we can change the world because we have many times before. You row forward looking back, and telling this history is part of helping people navigate toward the future. We need a litany, a rosary, a sutra, a mantra, a war chant of our victories. The past is set in daylight, and it can become a torch we can carry into the night that is the future.

Amen.